Gestational Diabetes

What you need to know!

Gestational Diabetes FAQs

What is gestational diabetes?

Diabetes mellitus (also called “diabetes”) is a condition in which too much glucose (sugar) stays in the blood instead of being used for energy. Health problems can occur when blood sugar is too high. Some women develop diabetes for the first time during pregnancy. This condition is called gestational diabetes (GD). Women with GD need special care both during and after pregnancy.

What causes GD?

The body produces a hormone called insulin that keeps blood sugar levels in the normal range. During pregnancy, higher levels of pregnancy hormones can interfere with insulin. Usually the body can make more insulin during pregnancy to keep blood sugar normal. But in some women, the body cannot make enough insulin during pregnancy, and blood sugar levels go up. This leads to GD.

If I develop GD, will I always have diabetes?

GD goes away after childbirth, but women who have had GD are at higher risk of developing diabetes later in life. Some women who develop GD may have had mild diabetes before pregnancy and not known it. For these women, diabetes does not go away after pregnancy and may be a lifelong condition.

Who is at risk of GD?

Several risk factors are linked to GD. It also can occur in women who have no risk factors, but it is more likely in women who

are overweight or obese

are physically inactive

had GD in a previous pregnancy

had a very large baby (9 pounds or more) in a previous pregnancy

have high blood pressure

have a history of heart disease

have polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

are of African American, Asian American, Hispanic, Native American, or Pacific Island background

How can GD affect a pregnant woman?

When a woman has GD, her body passes more sugar to her fetus than it needs. With too much sugar, her fetus can gain a lot of weight. A large fetus (weighing 9 pounds or more) can lead to complications for the woman, including

labor difficulties

cesarean delivery

heavy bleeding after delivery

severe tears in the vagina or the area between the vagina and the anus with a vaginal birth

What other conditions can a woman with GD develop?

When a woman has GD, she also may have other conditions that can cause problems during pregnancy. For example, high blood pressure is more common in women with GD. High blood pressure during pregnancy can place extra stress on the heart and kidneys.

Preeclampsia also is more common in women with GD. If preeclampsia occurs during pregnancy, the fetus may need to be delivered right away, even if it is not fully grown.

How can GD affect a baby?

Babies born to women with GD may have problems with breathing and jaundice. These babies may have low blood sugar at birth.

Large babies are more likely to experience birth trauma, including damage to their shoulders, during vaginal delivery. Large babies may need special care in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). There also is an increased risk of stillbirth with GD.

Will I be tested for GD?

All pregnant women should be screened for GD. Your obstetrician–gynecologist (ob-gyn) or other health care professional will ask about your medical history to determine whether you have risk factors for GD. If you have risk factors, your blood sugar will be tested early in pregnancy. If you do not have risk factors or your testing does not show you have GD early in pregnancy, your blood sugar will be measured between 24 weeks and 28 weeks of pregnancy.

If I have GD during pregnancy, how will I manage it?

You will need more frequent prenatal care visits to monitor your health and your fetus’s health. You will need to track your blood sugar and do things to keep it under control. Doing so will reduce the risks to both you and your fetus. For many women, a healthy diet and regular exercise will control blood sugar. Some women may need medications to help reach normal blood sugar levels even with diet changes and exercise.

How do I track blood sugar levels?

You will use a glucose meter to test your blood sugar levels. This device measures blood sugar from a small drop of blood. Keep a record of your blood sugar levels and bring it with you to each prenatal visit. Blood sugar logs also can be kept online, stored in phone apps, and emailed to your ob-gyn or other health care professional. Your blood sugar log will help your ob-gyn or other health care professional provide the best care during your pregnancy.

Should I change my diet if I have GD?

When women have GD, making healthy food choices is even more important to keep blood sugar levels from getting too high. If you have GD, you should eat regular meals throughout the day. You may need to eat small snacks as well, especially at night. Eating regularly helps avoid dips and spikes in your blood sugar level. Often, three meals and two to three snacks per day are recommended.

Also, it is important to gain a healthy amount of weight during pregnancy. Talk with your ob-gyn or other health care professional about how much weight gain is best for your pregnancy. For a woman with GD, too much weight gained or weight gained too quickly can make it harder to keep blood sugar levels under control.

Will regular exercise help me control GD?

Exercise helps keep blood sugar levels in the normal range. You and your ob-gyn or other health care professional can decide how much and what type of exercise is best for you. In general, 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise at least 5 days a week is recommended (or a minimum of 150 minutes per week). Walking is a great exercise for all pregnant women. In addition to weekly aerobic exercise, it’s a good idea to add a walk for 10–15 minutes after each meal. This can lead to better blood sugar control.

Will I need to take medication to control my GD?

For some women, medications may be needed to manage GD. Insulin is the recommended medication during pregnancy to help women control their blood sugar. Insulin does not cross the placenta, so it doesn’t affect the fetus. Your ob-gyn or other health care professional will teach you how to give yourself insulin shots with a small needle. In some cases, your ob-gyn or other health care professional may prescribe a different medication to take by mouth.

If you are prescribed medication, you will continue monitoring your blood sugar levels as recommended. Your ob-gyn or other health care professional will review your glucose log to make sure that the medication is working. Changes to your medication may be needed throughout your pregnancy to help keep your blood sugar in the normal range.

Will I need tests to check the health of my fetus?

Special tests may be needed to check the well-being of the fetus. These tests may help your ob-gyn or other health care professional detect possible problems and take steps to manage them. These tests may include the following:

Fetal movement counting (“kick counts”)—This is a record of how often you feel the fetus move. A healthy fetus tends to move the same amount each day. You should contact your ob-gyn or other health care professional if you feel a difference in your fetus’s activity.

Nonstress test—This test measures changes in the fetus’s heart rate when the fetus moves. The term “nonstress” means that nothing is done to place stress on the fetus. A belt with a sensor is placed around your abdomen, and a machine records the fetal heart rate picked up by the sensor.

Biophysical profile (BPP)—This test includes monitoring the fetal heart rate (the same way it is done in a nonstress test) and an ultrasound exam. The BPP checks the fetus’s heart rate and estimates the amount of amniotic fluid. The fetus’s breathing, movement, and muscle tone also are checked. A modified BPP checks only the fetal heart rate and amniotic fluid level.

Will GD affect the delivery of my baby?

Most women with controlled GD can complete a full-term pregnancy. But if there are complications with your health or your fetus’s health, labor may be induced (started by drugs or other means) before the due date.

Although most women with GD can have a vaginal birth, they are more likely to have a cesarean delivery than women without GD. If your ob-gyn or other health care professional thinks your fetus is too big for a safe vaginal delivery, you may discuss the benefits and risks of a scheduled cesarean delivery.

What are the future health concerns for women who had GD?

GD greatly increases the risk of developing diabetes in your next pregnancy and in the future when you are no longer pregnant. One third of women who had GD will have diabetes or a milder form of elevated blood sugar soon after giving birth. Between 15% and 70% of women with GD will develop diabetes later in life.

Women who have high blood pressure or preeclampsia during pregnancy also are at greater risk of heart disease and stroke later in life. If you had high blood pressure or preeclampsia during a past pregnancy, tell your ob-gyn or other health care professional so the health of your heart and blood vessels can be monitored throughout your life.

What are the future health concerns for children?

Children of women who had GD may be at risk of becoming overweight or obese during childhood. These children also have a higher risk of developing diabetes. Be sure to tell your baby’s doctor that you had GD so your baby can be monitored. As your baby grows, his or her blood sugar levels should be checked throughout childhood.

If I have GD, is there anything I should do after my pregnancy?

If you have GD, you should have a blood test 4–12 weeks after you give birth. If your blood sugar is normal, you will need to be tested for diabetes every 1–3 years.

Glossary

Amniotic Fluid: Water in the sac surrounding the fetus in the mother’s uterus.

Cesarean Delivery: Delivery of a baby through surgical incisions made in the woman’s abdomen and uterus.

Diabetes Mellitus: A condition in which the levels of sugar in the blood are too high.

Fetus: The stage of prenatal development that starts 8 weeks after fertilization and lasts until the end of pregnancy.

Gestational Diabetes (GD): Diabetes that arises during pregnancy.

Glucose: A sugar that is present in the blood and is the body’s main source of fuel.

Hormone: A substance made in the body by cells or organs that controls the function of cells or organs. An example is estrogen, which controls the function of female reproductive organs.

Insulin: A hormone that lowers the levels of glucose (sugar) in the blood.

Jaundice: A buildup of bilirubin that causes a yellowish appearance.

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU): A specialized area of a hospital in which ill newborns receive complex medical care.

Obstetrician–Gynecologist (Ob-Gyn): A physician with special skills, training, and education in women’s health.

Placenta: Tissue that provides nourishment to and takes waste away from the fetus.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A condition characterized by two of the following three features: 1) the presence of many small fluid-filled sacs in the ovaries, 2) irregular menstrual periods, and 3) an increase in the levels of certain hormones.

Preeclampsia: A disorder that can occur during pregnancy or after childbirth in which there is high blood pressure and other signs of organ injury, such as an abnormal amount of protein in the urine, a low number of platelets, abnormal kidney or liver function, pain over the upper abdomen, fluid in the lungs, or a severe headache or changes in vision.

Stillbirth: Delivery of a dead baby.

Ultrasound Exam: A test in which sound waves are used to examine internal structures. During pregnancy, it can be used to examine the fetus.

If you have further questions, contact your obstetrician–gynecologist.

FAQ177. Copyright November 2017 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

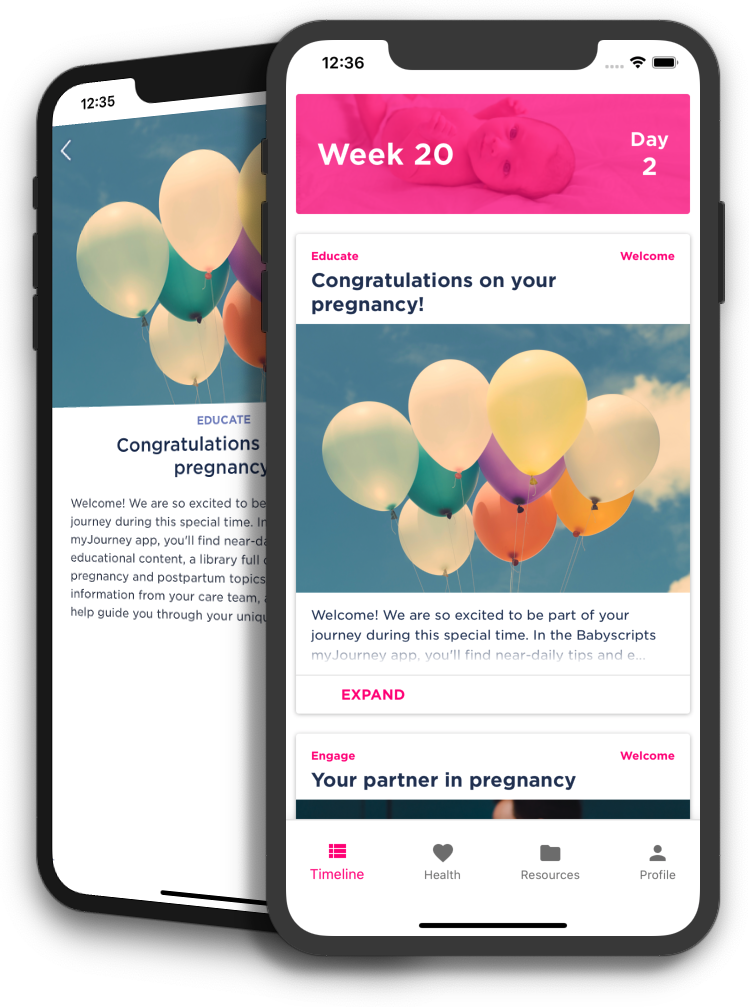

Want access to this content on your phone?

Access all of your provider-approved content through the Babyscripts app! Log in for daily gestation-specific content, a library of resources, weight tracking, and additional biometric tracking based on your provider's care plan.

Don't have it yet? Make sure to ask your provider for more information.